QUEER THEORY

The

Visibility Dilemma

Gamson (1998) succinctly expresses the basic dilemma of the critique of

lesbian gay, bisexual and transgendered people (LGBT) in popular culture. In

his book on The Jerry Springer

Show and other talk shows, he

talks of his mixed feelings watching the shows. On the one hand he was

horrified that LGBT folks are usually portrayed as freaks and predators. On the

other, he compulsively watched the shows because they were one of the only

places where he could see representations of LGBT people in the media.

Feminist

and racial anti-defamation activists have for a long time fought against both

negative stereotyping and lack of visibility. And for a long time there seems

to have been a consensus that visibility was not worth a negative stereotype.

This is more complex in LGBT circles, for a variety of historical reasons that

are unique to the history of LGBT folks in media.

The Hays Code,

or Motion Picture Production Code, which censored films from 1930 to 1968,

prohibited many things, including the depiction of drug use, nudity, childbirth, swear words, and homosexuality. This drove

Hollywood to shift its storytelling into more oblique ways. Biesen

(1995) analyzes how the noir film Double

Indemnity, which depicts a

wife using an insurance man to help her kill her husband by sexually

manipulating him, and which should have been censored by the Code, instead uses

metaphor and visual innuendo. As Biesen

argues, “the Code was rather ill-equipped to handle nuances” (p. 47).

Russo

(1987) (also see the Homosexuality

in Film page connected to

film version of Russo's book, The

Celluloid Closet) outlines many of the ways in which homosexuality

continued to exist in film as nuance: as a homophobic stereotype, and as

a more sensitive portrayal from the many closeted and (a few) out LGBT writers

and directors and actors making films at this time.

Sometimes this could be done very subtly, as

in this Celluloid Closet clip about

1959’s Ben-Hur:

There are two key elements to this nuance.

First, LGBT characters are indicated subtly, with slightly gender-bending

dress, and with a series of affectations that came to represent “gay” for a gay

filmgoing audience looking for it. A character might

have a very high pitched or wispy voice, overdress, carry a walking stick or

have a very specifically groomed mustache, for example. Audiences came to read

these things are representing what could not be explicitly represented. Second,

as Benshoff (1997) argues, anti-gay stereotyping,

which had always existed but was now hidden and nuanced, continued, especially

in the portrayal of villains as somehow strangely queer. This resulted in a set

of slightly coded “queer” and “less masculine” elements (according to the

hegemony of the times) as being shared signs indicating queerness and evil.

Compare the clear straightness of Humphrey

Bogart’s private eye in 1941’s The Maltese

Falcon with the more ambiguous Peter Lorre as Mr. Cairo:

Another good example is from Hitchcock, who

made a career out of ambiguously gay villains. Consider Robert Walker's (dark tie) character from 1951’s Strangers on a Train:

For women, the queer villain was somehow “inappropriately”

masculine and strong-willed. The following longish scene from Hitchcock’s

(again!) Rebecca (1940) is worth

watching until the end:

Gay filmmakers, like The Bride of Frankenstein's

James Whale, began to use this gay villain and gay monster figure as a sympathetic character, as

a monster who doesn't quite fit in. Benshoff traces

this over decades and hundreds of films. Here is Doctor Praetorius

in that film:

Thus we get to Gamson,

who grew up wanting that elusive visibility, but also grew up used to seeing

and empathizing with a gay villain. Because there is a celluloid closet where

gay actors and characters can pass for straight, this is a unique dilemma.

There are unfortunate legacies in current

film as a result of this, though. Scar in 1994’s The Lion King, for example, seems to be another coded gay villain:

He certainly lacks masculinity compared to Mufasa, the literal patriarch who leads the community to

worshipping straight male fertility on the phallic pride rock:

Scar, instead, slinks off into the folds of

rock behind the phallic protrusion:

In a 90s twist, this crypto-gay villain

represents death and lack of productivity not just as a kind of antithesis to

the overdetermined worship symbolism of life and

procreation in the film, but in terms of literal death that we might associate

with AIDS-centered homophobia of that time. He (or his minions) preys on kids

in a graveyard, murders Mufasa, and runs a fascist

coup of lazy hyenas who take fertility and destroy it:

He even apparently wears the same eye makeup

as Disney’s past butch female villains:

Homophobia

The

idea and the term homosexual was invented

in the 1800s, when sex between members of the same gender was labeled as a

medical condition. Previous to this, people were simply people who had sex with

whatever types of people they were having sex with. Sexual behaviors were not

considered determinant of person or personality. But once medicine and the

emerging field of psychology began to label it and argue that it was a syndrome

or a disease, negative public reaction to same-sex sexuality began to rise.

This term, homosexual, which defines a person solely in terms of their sexual

behavior, is considered objectionable by a number of gays and lesbians.

As

an anti-gay ideology developed and strengthened throughout twentieth century

America, the hatred and oppression of gays and lesbians began to take a very

specific form. Hate and fear are likely conjoined in many cases, but this seems

especially true for anti-gay sentiment. Homophobia is a term which describes the fear of

homosexuality. Fears that homosexuals will be attracted to or make passes at

heterosexuals are commonly spoken of. That a man on Jenny Jones would be driven to murder by the

confession of a gay neighbor's crush is testimony to the extent of this fear. A

certain form of hysterical masculinity develops, with jokes about bending over

to pick up the soap in the shower, etc., as a part of this homophobic ideology.

Both straight men and straight women often have violent physical reactions to

scenes of gay and lesbian kisses (McKee, 1996), and it seems that this is out

of proportion with their (admitted or not) level of anti-gay hatred. Does fear

drive us on this issue more than we think?

Look at this scene from 1974’s Freebie and the Bean:

Ron Nyswaner,

interviewed in The Celluloid Closet, interprets this scene as a kind of

over-the-top hysterical hatred of the transsexual character, especially at the

very end. The level of violence indicates hatred. But the question in terms of

this idea of homophobia is whether or not fear is the primary element. It is

probably an unanswerable question.

The

Howard Stern phenomena of men being interested in lesbians seems to indicate

that homophobia is somehow personalized. Homophobia, then, seems to explain

Howard and lesbians. Males who want to see hard core pornography but feel their

homophobia rise when gazing at men having sex would seem to be suited for

lesbian porn, where there aren't any threatening thrusting penises. The high

rate of transvestite and transsexual prostitutes murdered by their johns seems

to also show that when that fear is realized, violence seems to be the

response.

And the aggressively (hysterically?)

disgusted responses to gay kissing is, for McKee, not the same as violence,

clearly, but a structurally similar overreaction. This “I just don’t want to

see it” phenomenon, which is still common, is often reported as an

all-inclusive “I don’t like to see anyone kissing, really,” which is just not

true for most of the people who would say it. This kind of kiss, from 1982’s Deathtrap, with Christopher Reeve and

Michael Caine, is so much more objectionable to the homophobic than the

millions of straight kisses in the media. It is as if the fear is also a fear

of simple visibility itself:

Any oppressed group who is "other"ed is usually feared,

but homophobia seems a bit a bit more persistent than others. Some have

explained homophobia as "latent" homosexual impulses being repressed

by the psyche and displaced onto others. Perhaps sometimes this is the case.

Perhaps, from the straight male perspective (the population for whom homophobia

most often turns into violence), the fear of being penetrated is so strong

because of our patriarchal notions about sex. Heterosexual sex, especially the

type by and for men where the woman's needs are less than important, often

seems to be an assertion of manliness, virility and phallic power. This might also

be why revelations that "manly" actors like Rock Hudson and Cary

Grant were gay or bisexual were so scandalous. Our images of masculinity seem

to require a certain kind of patriarchal sexuality that is denied in a gay

setting. If a straight man is penetrated and "becomes the woman" he

becomes weak, according to their type of homophobia.

But whatever the origins or nature of

individual homophobias, the intensity of questions of the visual underscores

another phenomenon from advertising in an interesting way.

A

final element that links this section with the previous one is Clark's (1991)

notion of gay window

advertising. The LGBT community is often seen by advertisers as a lucrative

market, but an explicitly gay ad might draw the homophobic ire of some straight

audiences. But since the LGBT community is historically trained to pick out

nuanced clues to identify gayness, these sorts of ads generally are able to

have it both ways. Straights don't notice. Gays do. And

example would be an ad a saw years ago but haven't

been able to find a copy of since. It is for a car. Two men are fishing and

camping. It looks like astraight beer commercial, but

the men are celebrating with glasses of white wine. Okay, that goes with fish,

so maybe this is just a class thing, but then you see they are sharing a

one-man pup tent if you look closer. They will be sleeping very close to each other that night. The

following image, which is unfortunately too small to see clearly, is another

example. A shirtless man in bed surrounded by art and posters of home décor, in

his curtained and rug-ed room with potted plants. Is

he straight? For gay readers, the answer to his sexuality is clear enough:

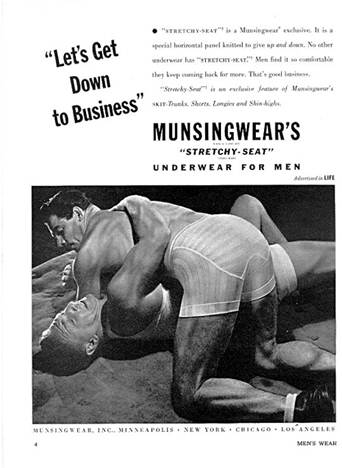

A few other examples:

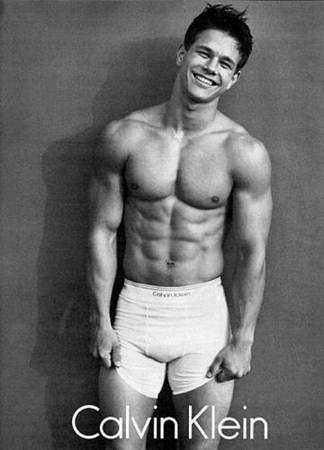

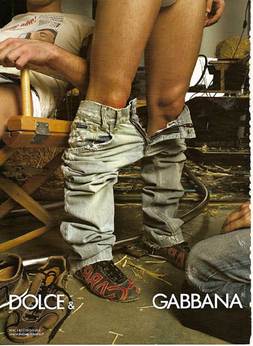

Calvin Klein pushed the boundaries of

straight and gay advertising so much over the past 20 years that now Dolce

& Gabbana can be more explicit:

Heteronormativity

It

is impossible, then, to separate notions of homosexuality from our notions of

gender. Judith Butler (1989) has argued that gender is not only socially

constructed but that it is also performance. It is a short leap from saying

that if our gender, which seems to be primarily performed through our

sexuality, is changeable and adaptable that our sexuality might also be. This

is one of the bases of queer

theory, the idea that people are not either heterosexual or homosexual, but

that such categories are taught and learned and performed. This is influenced

by a postmodernism which is suspicious of all such binaries as

homosexual-heterosexual. The growing recognition of bisexuals, transvestites

and transsexuals is part of a growing idea that gender and sexuality are much

more malleable than we generally think. Such people, generally grouped under

the term transgendered, are

people whose existence challenges our notions of gender roles and of sexual

orientation.

Queer

theorists picked that particular term to describe themselves

based on the political activism of Queer Nation, which attempted to take a

derogatory term and change its meaning for good. It is a term which is used

because it is more inclusive and avoids the problem of words like "homosexuality,"

which reduce people to merely their sexual acts.

This

idea is very controversial, in and out of the gay community. There is fairly

convincing evidence that homosexuality is at least partially genetic. The LeVay (1991) studies on the hypothalamus in the brain seem

to indicate that there are differences in brain makeup and chemistry between

the gay and the straight. . The testimony of people who feel they were

"born gay" also cannot be discounted. At the very least, the hell

that most teens go through when they come out should seriously argue against

the idea that gayness is in any way a choice (who, really, would choose that?).

Queer

theory seems to negate such ideas, in its argument that, in one version of it,

we are all queer (this does not necessarily mean we are all bisexual, as you

may have heard on TV; but it does mean that all of our sexualities are far more

negotiable than we might think). The message of queer theory might be

assimilated into that of the fundamentalists who try to "convert" gay

people into straight people. It might be used by those who argue a

pseudoscience that gay people (especially lesbians) become that way due to

trauma in childhood (This argument is made by some gay people, as well. The

problem with it is that it overgeneralizes from a few examples. Plus,

considering the great number of women who are sexually abused while young, the

likelihood that a lesbian will have been sexually abused as well would then

also be high, especially if the abusers had picked up on some kind of queerness

and did some perverted attempt to "fix" her; an occurrence which has

also been reported. At the very least, the fact that this argument is almost

solely applied to women should make us suspicious of the underlying sexism that

is only comfortable with women when they are portrayed as victims. Indeed, how

is it that abuse by, say, an uncle, is supposed to have the same

"queering" effect on both a boy and a girl? The argument doesn’t make

sense).

At

the same time, though, although such evidence is helpful in answering a

religious debate (if people are actually born gay, there is no way a creator

God could condemn such people, goes the argument), it also feeds into the

psychological homophobia. If there is a "gay" part of the brain in

people, then some would consider it a defect to be cut out. Queer theory, in

arguing against the existence of such a thing as heterosexuality and

homosexuality, becomes the radical answer to such perspectives. Its importance

lies not so much in its negation of the idea of homosexuality (which has its

problems), but in its negation of the idea of a unified heterosexuality. If

there is no heterosexuality, all of the ammunition of the anti-gay ideology

begins to misfire.

Of

course, if queer theory is right, that might be another explanation for the

robustness of homophobia. Heterosexuals are afraid of losing the privilege and

gender stability that the idea of heterosexuality provides. Historically, the

idea of a unified heterosexuality is very recent. As mentioned previously,

sexual behaviors were, for most of history, not things which identified a whole

"orientation." They were merely acts which were either punished or

not. There was never any contradiction in a straight (and even married) man

having sex also with men.

This

brings us finally to the relevance of this for popular culture. Not only is

popular culture still notoriously homophobic (showing gays and lesbians as

dangerous and predatory and monstrous more often than not) but it also

expresses heteronormativity.

This is the presentation of a naturalized heterosexuality. It is as if all

people are straight. Or at least they are assumed to be unless it is proven

otherwise. Just as, in books, a character is assumed to be white unless we are

told otherwise, the same is true for heterosexuality. In almost every facet of

life we are presented with the heteronormative.

A

classic example of this is the popular show Will

and Grace. Character and plot bend to make it as if Will and Grace are a couple with their child, the infantile Jack (Battles

& Hilton-Morrow, 2002). This is probably why the show was acceptable to

straight audiences. It still reinforces the primacy of the straight style or

way of life. Just like the notion that in any gay couple there is one who is

the “man” and one who is the “woman.”

Conclusion

Questions of visibility, homophobia and heteronormativity are clear in this episode of the web

series Husbands. Think of how the

characters struggle with what kinds of visibility are allowed and not in 2012.

Think of how nonheteronormative this show is compared

to Will and Grace. The first season

of this show was less heteronormative than this

episode, but as they respond to homophobia, you can see the characters

struggling to define their roles. Finally, these characters clearly have sex in

a way that only straight couples are allowed to talk/joke about in mainstream

television. If you watch Modern Family,

there are episodes about Phil and Claire’s sex lives, but never Cameron and

Mitchell.

In a post-Glee

world where Curt’s dad defended his son against the f-word, where gay marriage

is happening, it seems like, everywhere but Chick-fil-A

maybe, things are changing. But where are the hegemonic dead ends?

By

Steve Vrooman, revised March 2013

References

Battles, K., & Hilton-Morrow, W. (2002). Gay characters in

conventional spaces: Will and

Grace and the situation

comedy genre. Critical Studies

in Media Communication, 19,

87-106.http://bulldogs.tlu.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ufh&AN=7385643&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Benshoff, H. (1991). Monsters in the closet:

Homosexuality and the horror film. Manchester UP.

Biesen, S.

(1995).

Censorship, film noir, and Double

Indemnity. Film & History, 25, 40-52. http://bulldogs.tlu.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ufh&AN=16900382&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Butler,

J. (1989). Gender

trouble. New York: Routledge.

Clark, D. (1991) Commodity lesbianism. Camera Obscura, 9, 181-201.

Gamson, J. (1998). Freaks

talk back: Tabloid talk shows and sexual nonconformity. U Chicago P.

LeVay, S. (1991). A

difference in hypothalamic structure between heterosexual and homosexual men. Science, 253, 1034-1037. http://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=sites&srcid=c2ltb25sZXZheS5jb218d3d3fGd4OmJkYmZiNDczOGMxNjU4MQ

Mckee, A. (1996). A kiss is just. Australian

Journal of Communication, 23,

51-72.

Russo, V. (1987). The celluloid closet: Homosexuality in the movies. NY: Harper.